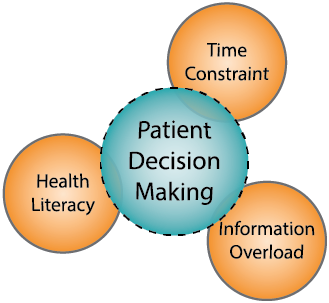

Making a balanced decision in every situation is an art, and when it comes to our health, it becomes very difficult because multiple factors are involved. Like any other situation, some aspects are within our control, while others are external and beyond our influence. Interplaying with these factors and effectively using them can assist both healthcare professionals and patients to make sound decisions. Lilford, et al. have previously discussed the significance of decision aids in maternity care, emphasising their role in improving patient satisfaction and reducing decisional conflict.[1, 2] Their work also explored how one-to-one coaching enhances communication styles among healthcare professionals. Additionally, the paradox of non-directive counselling highlighted challenges in providing unbiased information while ensuring informed decision making. In this blog, I will discuss three important factors in patient decision-making that, if balanced correctly, can lead to better outcomes.

The First Musketeer: Time Constraint (Athos, the Wise but Limited Leader)

Time constraints in clinical settings often impede comprehensive patient discussions. Healthcare professionals have little time to explain options, which leaves patients struggling to make informed decisions. When time is limited, people often amplify the framing effect, becoming more willing to take risks in loss frames and more cautious in gain frames. Shorter deadlines increase the chances of making impulsive decisions based on how options are framed. When individuals face higher pressure to make a decision quickly, they rely more on their initial instincts rather than rational analysis.[3] Therefore, neutral framing of time is very important. For example, the maternity theme of the NIHR Midlands Patient Safety Research Collaboration (PSRC) is working on a project to help patients make optimal decisions, and there is a need to use neutral framing in this context to avoid influencing decisions based on fear or urgency. For instance, instead of saying, “if you wait, then your baby may grow too big, increasing risks,” re-frame it as “early decision-making allows for more options and better preparation.”

Primary care physicians frequently feel that time constraints hinder their ability to engage in thorough shared decision-making with patients.[4] It creates pressure in the decision-making process, particularly in healthcare settings where patients and clinicians need to make informed choices quickly. Using a multi-modal approach that combines verbal discussions with written leaflets, infographics, and digital resources is essential. These methods can significantly improve the decision-making process. We should guide patients through all these options, as leaflets and infographics provide visual representation of key information that patients can easily digest. Additionally, we can reschedule appointments and suggest credible web pages, allowing patients to explore the information at their own pace, without feeling rushed, enabling them to make better decisions.[5]

The Second Musketeer: Health Literacy (Porthos – The Strong but Needs Clarity)

Patients with low health literacy may struggle to understand complex medical information, which hinders their ability to comprehend the details, risks, and associated benefits, leading to suboptimal decisions. McCaffery, et al. recommended in their research that patient decision aids should be developed to cater to patients with different health literacy needs.[6] They suggested incorporating plain language, visual aids, and interactive elements can enhance comprehension and usability for patients with limited health literacy. Ensure that the language used in the patient decision aid is suitable for the comprehension levels of the majority of the target audience by employing a quantifiable strategy (e.g., Flesch-Kincaid, Simple Measure of Gobbledegook (SMOG), Fry Readability Formula (or Fry Readability Graph), or other recognised methods).[7] These tools offer a quantifiable means to align the material’s complexity with the reading abilities of the intended audience. Nevertheless, it’s crucial to recognise that while these formulas provide valuable insights, they have limitations. In short, we can tackle health literacy by simplifying the information for the patient, ensuring that we explain it in an easy-to-understand language. After explaining, we should check their understanding by asking, “What did you understand from this?” or “Is there anything you would like me to explain again?”

Additionally, we can schedule follow-up appointments to give them time to process the information and return with any questions. We can also suggest they bring a family member or someone knowledgeable about these matters for support. Furthermore, we can send them an email summarising the key points and inviting them to reach out if they need further clarification.

It is important to present health information in a way that most adults can read, comprehend, and make informed decisions.

The Third Musketeer: Information Overload (Aramis – The Idealist, but Overwhelmed by Choices)

Excessive data can confuse rather than clarify, making decision-making overwhelming instead of empowering. The information doctors provide isn’t always equally important for every patient. One type of information may be crucial for one set of patients but not for others because their circumstances differ. Providing too much information can overwhelm patients, making it difficult for them to make decisions. So it’s essential to tailor the tone, type of information, and context to each patient’s unique circumstances.[8]

We can adopt strategies to avoid information overload, helping patients make better decisions. It’s crucial to provide a clear, balanced, and neutral presentation with objective, complete, and evidence-based information. Highlight key features and present information side by side to allow patients to compare benefits and risks easily. Mixed media, like videos, can be more engaging and unbiased. Using pictographs and numerical formats helps patients make better decisions. Avoid words that favour one option over another and present positive and negative aspects equally. Chunk the information into layers to prevent overload and offer progressive disclosure for step-by-step details. Tailor the information to the patient’s health literacy level, ensuring it’s digestible for them.[9]

These decision aids are vital tools that bridge the gap between patient empowerment and medical knowledge. Their effectiveness relies on addressing three key aspects: time constraints, health literacy, and information overload. By effectively addressing these, we can streamline decision-making through clear, accessible communication, turning challenges into opportunities for better engagement. The true essence of patient decision aids lies in presenting information and guiding patients toward decisions aligned with their values, preferences, and unique health journeys. The balance we strike today between depth and acceptability will define the future of patient-centred care.

Therefore, we must empower individuals to make confident, clear, and controlled choices. Solutions should address all three simultaneously, improving communication, simplifying complex information, and allowing sufficient time for decision-making.

— Saba Tariq, Post-doctoral Fellow.

References:

- Lilford R. One-to-One Coaching Improves Cardiologists’ Communication Style. NIHR ARC West Midlands News Blog. 2023; 5(4): 6.

- Lilford R. The Information Paradox at the Heart of Non-Directive Counselling. NIHR ARC West Midlands & Midlands PSRC News Blog. 2024; 6(4): 1-2.

- Diederich A, Wyszynski M, Traub S. Need, frames, and time constraints in risky decision-making. Theory Decision. 2020; 89(1): 1-37.

- Konrad TR, Link CL, Shackelton RJ, et al. It’s about time: physicians’ perceptions of time constraints in primary care medical practice in three national healthcare systems. Med Care. 2010; 48(2): 95-100.

- Kline A, Wang H, Li Y, et al. Multimodal machine learning in precision health: A scoping review. NPJ Digit Med. 2022; 5(1): 171.

- McCaffery KJ, Holmes-Rovner M, Smith SK, et al. Addressing health literacy in patient decision aids. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2013; 13(s2): s10.

- McCaffery K, Sheridan S, Nutbeam D, et al. Chapter J: Addressing Health Literacy. In: Volk R & Llewellyn-Thomas H (eds). 2012 Update of the International Patient Decision Aids Standards (IPDAS) Collaboration’s Background Document.

- Lilford R. Decision Aids to Help People Make Difficult Decisions. NIHR ARC West Midlands & Midlands PSRC News Blog. 2024; 6(5): 1-4.

- Martin RW, Brogård Andersen S, O’Brien MA, et al. Providing balanced information about options in patient decision aids: an update from the International Patient Decision Aid Standards. Med Dec Mak. 2021; 41(7): 780-800.